Become SERBIAN

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

DIVE INTO A LIFESTYLE

From its founding in 896 AD by the Slavic tribes, through its medieval kingdoms and Ottoman rule, to its emergence as part of Yugoslavia, Serbia has played a pivotal role in Balkan history. Its cultural heritage reflects influences from Byzantine, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian rule, blended with deeply rooted Slavic traditions. With its stunning architectural heritage, from medieval monasteries to Belgrade’s dynamic urban landscape, Serbia offers a timeless journey through its rich and diverse cultural legacy.

After the fall of communism and the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Serbia underwent a remarkable transformation. The nation embraced political and economic reforms, seeking integration with European institutions while maintaining its strong national identity. Its thriving arts scene, expanding tourism industry, and focus on education and technology showcase a country that honors its past while forging a bright future. Today, Serbia is a bridge between East and West, celebrated for its unique language, cuisine, and resilient spirit.

We have created a selection of words and expressions that you won’t find in any textbook or course, designed to make you sound like a true native by helping you understand Serbian words that carry a deeper cultural meaning, as well as expand your knowledge of the country and its history.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Serbian, we recommend that you download the Complete Serbian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't in any other textbook so you can amaze your Serbian friends with your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Serbian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Serbian today!

AJVAR

Ajvar (roasted red pepper relish) is one of the most emblematic foods of Serbian cuisine, representing both tradition and seasonal community work. The preparation of ajvar usually takes place in early autumn when red peppers are at their peak. Families and neighbors gather to roast, peel, and grind the peppers before cooking them slowly with oil and salt in large pots. This process can take several hours and often turns into a social event filled with conversation and laughter.

Historically, ajvar was considered a winter preserve, stored in glass jars and eaten as a spread on bread or as a side dish with grilled meat and bread known as lepinja (flatbread). It originated in the regions around Niš and Leskovac, where the mild climate produces high-quality peppers. Over time, it became a staple across Serbia, North Macedonia, and the wider Balkans, though Serbs consider their version the most authentic.

In Serbian households, ajvar is seen not just as food but as a symbol of home life and continuity. Its preparation connects generations, as recipes are passed from grandmothers to younger family members. The taste can vary from mild to spicy, depending on whether chili peppers are added, and some families enrich it with eggplant or garlic.

Economically, ajvar production also supports rural areas. In recent years, artisanal and industrial producers have begun exporting ajvar internationally, labeling it as a “Serbian specialty.” Festivals such as the Ajvarijada (Ajvar Festival) in Leskovac celebrate the tradition with competitions for the best homemade relish.

Culturally, ajvar is deeply linked to the idea of Serbian hospitality. It is served alongside roštilj (grilled meat), sir (cheese), and rakija (fruit brandy), forming part of the classic Serbian meal that reflects both simplicity and richness. Even among Serbs living abroad, ajvar remains a powerful reminder of home, often prepared in smaller quantities to preserve the taste of national identity.

In modern cuisine, chefs have begun experimenting with ajvar in sandwiches, pasta sauces, and even gourmet dishes, yet its essence remains tied to rural life and the collective memory of autumn kitchens filled with the smell of roasted peppers.

BATTLE OF KOSOVO

Battle of Kosovo – Kosovo Polje (historic 1389 battle that shaped Serbian identity) is one of the most significant events in Serbian history and collective memory. Fought on June 28, 1389, between the forces of Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović and the Ottoman army led by Sultan Murad I, the battle took place on the plains of Kosovo, known as Kosovo Polje (Field of Blackbirds). Although its military outcome remains debated, its cultural and symbolic importance for Serbia is immense.

The confrontation marked a turning point in the medieval Serbian state’s struggle against Ottoman expansion. Prince Lazar’s army, composed of nobles, knights, and peasants, faced a much larger Ottoman force. Both leaders—Lazar and Murad—were killed in battle, and although the Ottomans ultimately gained dominance, the Serbs preserved the event as a story of heroism and moral victory rather than defeat. The notion of kosovski zavet (Kosovo vow), symbolizing sacrifice for faith and nation, emerged from this event and became a cornerstone of Serbian identity.

The battle’s legacy was transmitted through epic poetry sung by guslars (epic bards), who kept the memory alive across centuries of Ottoman rule. Figures such as Miloš Obilić, said to have slain the Sultan, and Kneginja Milica, Prince Lazar’s widow who ruled as regent, became enduring national heroes. These narratives established ideals of loyalty, honor, and self-sacrifice that continue to shape Serbian national consciousness.

Vidovdan (St. Vitus Day), celebrated on June 28, commemorates the battle and carries profound religious and patriotic meaning. On this day, the Serbian Orthodox Church holds liturgies, and national ceremonies take place at the Gazimestan Monument, erected near the battlefield. The battle has also influenced art, literature, and politics, often invoked during times of national crisis as a symbol of resilience and unity.

In modern Serbia, the Battle of Kosovo remains a subject of both reverence and debate. While many view it as a sacred foundation of national history, others see its mythologization as a barrier to reconciliation and modernization. Nonetheless, Kosovo Polje occupies a central place in Serbian historical consciousness, intertwining medieval heritage with modern national identity.

The enduring presence of this event in education, religious tradition, and cultural expression reflects its role not only as a historical occurrence but as a living symbol of faith, sacrifice, and continuity in Serbian culture.

BUREK

Burek (flaky pastry filled with meat, cheese, or spinach) is one of the most recognizable dishes in Serbian cuisine and an everyday favorite across the Balkans. It consists of thin layers of kore (phyllo dough) filled with savory ingredients and baked until golden and crisp. The most traditional Serbian version is round and usually filled with minced meat, though variations with cheese (sir), spinach (zelje), or potatoes (krompir) are equally popular.

The origins of burek trace back to the Ottoman Empire, where similar pastries were introduced from Anatolia and gradually spread throughout the Balkans. In Serbia, the earliest records of burek date to the eighteenth century, with the city of Niš often cited as the place where it took on its distinctive round form. The pastry quickly became a symbol of urban street food, sold in pekare (bakeries) across the country, especially as a morning meal served with yogurt or sour milk.

Preparing burek requires skill and patience. The thin dough layers are stretched by hand, filled, and rolled or coiled before being baked in a circular pan called a sač (baking tray). A perfectly baked burek has a crispy exterior and soft interior, balancing textures and flavors. Although industrial production has made burek widely available, traditional handmade methods remain highly valued for authenticity and taste.

Culturally, burek has become part of daily life in Serbia, transcending class and regional divisions. It is eaten for breakfast, lunch, or as a late-night snack after social gatherings. Debates about what counts as “true burek” are common; in Belgrade, for example, many insist that only the meat-filled version deserves the name, while others accept cheese or vegetable varieties as legitimate.

Beyond its culinary appeal, burek has social significance. It represents the shared cultural heritage of the Balkans and the blending of Ottoman and Slavic influences. Festivals such as the Buregdžijada (Burek Festival) in Niš celebrate local bakers and honor the craft of burek-making, attracting thousands of visitors annually.

In modern Serbia, burek continues to evolve. Contemporary chefs experiment with new fillings like mushrooms, leeks, or even chocolate, while maintaining the essential character of the dish. Whether eaten in a small village bakery or a Belgrade café, burek remains a national comfort food—simple, hearty, and deeply tied to everyday Serbian identity.

ČESNICA

Česnica (ceremonial bread prepared for Orthodox Christmas) is one of the central elements of Serbian Christmas traditions, symbolizing unity, faith, and family prosperity. The bread is baked on Badnje veče (Christmas Eve) or early on Christmas Day and holds deep religious and cultural meaning. Its preparation follows specific rituals passed down through generations, blending Christian symbolism with ancient Slavic customs tied to fertility and renewal.

Traditionally, česnica is made from simple ingredients—flour, water, and salt—without yeast. The woman of the household kneads the dough silently, often making the sign of the cross over it three times before baking. A coin is inserted into the dough before it is placed in the oven, representing luck and blessing for the coming year. When the bread is baked, it is not cut with a knife but rather broken by hand among all family members, symbolizing togetherness and equality before God.

During the Christmas meal, the head of the family turns the česnica three times in a clockwise direction while saying prayers. Each family member then takes a piece, and the person who finds the coin is believed to receive good fortune and health throughout the year. In rural areas, other small objects like a bean, grain, or wooden cross may also be hidden in the bread, each carrying a different symbolic meaning related to wealth, fertility, or faith.

The design of česnica varies by region. In some parts of Serbia, it is decorated with dough ornaments such as crosses, doves, vines, and ears of wheat, representing peace, abundance, and life. In the Vojvodina region, butter and eggs are sometimes added, while in southern Serbia, the bread remains plain but firm. Despite these variations, the central meaning remains consistent: česnica is not merely food but a sacred offering connecting the household to divine grace.

Over time, the ritual of česnica has expanded beyond private homes to communal and church celebrations. In cities, churches organize gatherings where large ceremonial breads are blessed by priests and shared among parishioners. Even among the Serbian diaspora, baking česnica has remained a vital part of maintaining cultural identity abroad.

The enduring presence of česnica in Serbian Christmas customs highlights its dual function as both a religious symbol and a cultural artifact. It represents continuity between past and present, uniting faith, family, and tradition in one simple yet profound act of sharing bread.

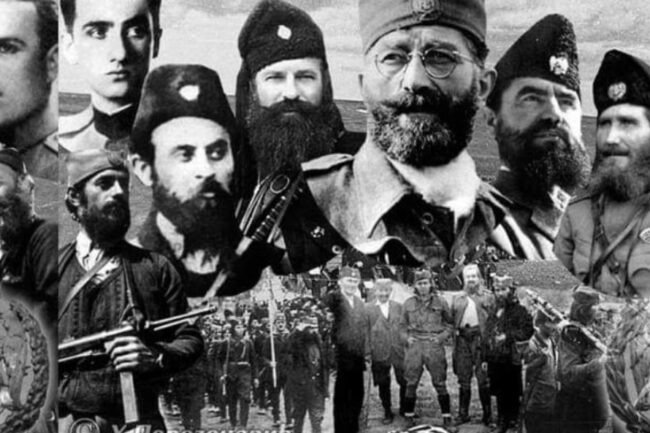

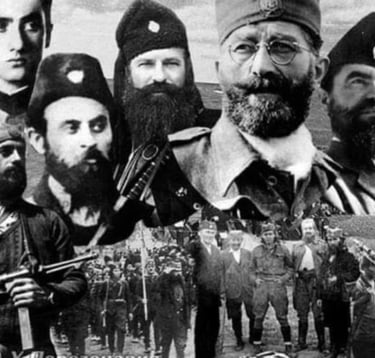

ČETNIK

Četnik (royalist guerrilla fighter originally from the 19th century, revived in WWII) refers to members of Serbian nationalist and monarchist movements that emerged during different historical periods. The term originated in the early nineteenth century, during the resistance against Ottoman rule, when armed bands known as čete (military detachments) fought for national liberation. These fighters were considered defenders of pravoslavlje (Orthodoxy), otadžbina (homeland), and narod (the people), embodying ideals of courage and loyalty to the Serbian crown.

In the twentieth century, the Četnički pokret (Chetnik movement) gained renewed importance during World War II under the leadership of Draža Mihailović, an officer of the Jugoslovenska vojska u otadžbini (Yugoslav Army in the Homeland). This movement aimed to restore the Kraljevina Jugoslavija (Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and resist both Axis occupation and communist forces led by partizani (partisans). Initially recognized by the Allies, Mihailović’s Chetniks later lost support as accusations of collaboration with Axis forces and conflicts with the Partisans intensified.

The wartime role of the Chetniks remains one of the most debated subjects in Serbian historiography. Some view them as patriots who fought to preserve the monarchy and national unity, while others see them as opportunistic groups whose actions included reprisals against civilians. After the war, the new komunistička vlast (communist government) condemned and outlawed the movement, branding it as traitorous and reactionary. Mihailović was captured, tried, and executed in 1946, and the Chetnik legacy was officially suppressed for decades.

Despite this suppression, Chetnik symbolism persisted underground and later resurfaced in the 1990s during the breakup of Yugoslavia. Some nationalist groups adopted the iconography of the old Chetniks, including the black šajkača (traditional Serbian cap) and insignia featuring the skull and crossbones with the slogan “Za kralja i otadžbinu” (For the king and the homeland). This revival reflected both historical nostalgia and political division in post-communist Serbia.

In the 2000s, the Serbian state began a process of historical reassessment. Mihailović was officially rehabilitated in 2015, recognizing him as a victim of a politically motivated trial. Monuments and memorial services honoring Chetnik fighters have since been established, particularly in regions with strong monarchist sentiment.

Today, the concept of the Chetnik carries complex meanings in Serbian society. It stands at the crossroads of history, nationalism, and identity, representing both a struggle for freedom and the enduring controversies of Serbia’s twentieth-century past. Its image continues to provoke reflection on loyalty, ideology, and the legacy of war.

ĆEVAPČIĆI

Ćevapčići (small grilled minced meat sausages served with flatbread) are one of the most iconic dishes in Serbian and Balkan cuisine. These cylindrical portions of minced meat, typically made from a mixture of junetina (beef), svinjetina (pork), and sometimes jagnjetina (lamb), are seasoned with salt, pepper, and garlic before being grilled over an open flame. Served hot with lepinja (flatbread), luk (onion), and ajvar (roasted pepper relish), ćevapčići represent both a national specialty and a shared regional culinary heritage.

The dish has its origins in the Ottoman kebab, which spread throughout the Balkans during centuries of Turkish rule. Over time, local variations developed across the region—Bosnia, Serbia, North Macedonia, and Montenegro each created distinct versions based on spice combinations, meat ratios, and preparation methods. In Serbia, particularly in cities like Leskovac and Novi Pazar, ćevapčići have become a symbol of traditional roštilj (barbecue) culture, which occupies a central place in Serbian gastronomy.

Preparing ćevapčići requires careful attention to texture. The minced meat is mixed thoroughly until it achieves a smooth consistency and is left to rest before grilling. Skilled grill masters, known as roštiljdžije (barbecue cooks), use charcoal-fired grills called skara, ensuring that each portion achieves a smoky aroma and juicy interior. The dish is often accompanied by kajmak (creamy dairy spread), pita (pie), and kiselo mleko (sour milk), forming a complete and hearty meal.

Beyond its culinary importance, ćevapčići hold social and cultural significance. They are a staple at family gatherings, festivals, and public celebrations such as the Roštiljijada (Barbecue Festival) in Leskovac, which attracts thousands of visitors each year. The festival not only promotes local food culture but also celebrates Serbian hospitality, where sharing grilled meat and rakija symbolizes friendship and community spirit.

In the Serbian diaspora, ćevapčići serve as a powerful reminder of home. Serbian restaurants abroad often feature them as a national dish, appealing to both expatriates and foreigners eager to taste authentic Balkan cuisine. The simplicity of ingredients and the communal nature of grilling make ćevapčići an enduring emblem of Serbian everyday life.

Today, ćevapčići occupy a prominent place in the national food identity, bridging traditional and modern cuisine. Whether sold in pekare (bakeries), restorani (restaurants), or street stalls, they embody the essential elements of Serbian food culture: craftsmanship, conviviality, and the joy of shared meals under the open sky.

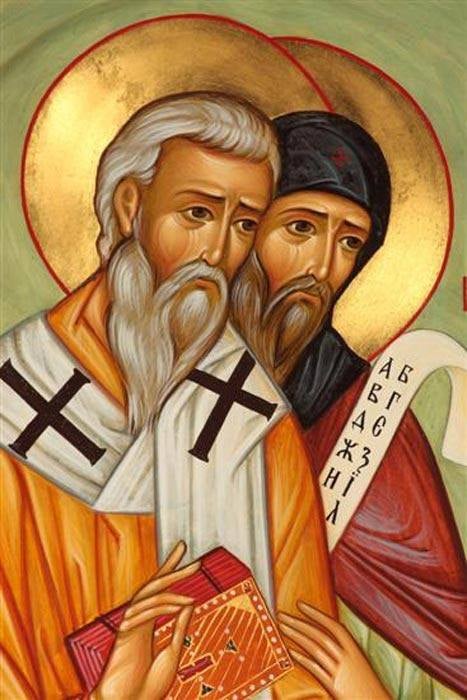

ĆIRILICA

Ćirilica (Cyrillic script) is one of the two official alphabets used in Serbia, alongside latinica (Latin script), and is regarded as a key element of national and cultural identity. The script was introduced to Slavic peoples in the ninth century by disciples of Saints Ćirilo i Metodije (Cyril and Methodius), Byzantine missionaries who developed the earlier glagoljica (Glagolitic script). Over centuries, ćirilica evolved through different forms, becoming the dominant writing system of the Serbian Orthodox Church, administration, and literature.

During the medieval period, Serbian ćirilica developed unique regional features. The earliest known examples appear in documents such as Miroslavljevo jevanđelje (The Miroslav Gospel), an illuminated manuscript from the twelfth century considered a masterpiece of early Serbian literacy and religious art. Monasteries like Studenica, Žiča, and Hilandar played central roles in preserving and copying texts in the Cyrillic script, ensuring continuity of written culture through turbulent historical periods.

With the rise of the Srpska pravoslavna crkva (Serbian Orthodox Church), ćirilica became deeply tied to religious life and spiritual identity. It remained the official script under medieval rulers of the Nemanjići dynasty and later served as a unifying cultural tool during Ottoman occupation, when maintaining literacy in Serbian was an act of resistance and faith. In the nineteenth century, linguist Vuk Stefanović Karadžić reformed the Serbian language and standardized the alphabet according to the principle “Piši kao što govoriš” (Write as you speak), simplifying ćirilica into the modern 30-letter form used today.

In socialist Yugoslavia, both ćirilica and latinica were officially recognized, reflecting the state’s policy of equality among South Slavic peoples. However, Latin script gained broader use in urban areas, education, and mass media, especially in mixed-language regions. In modern Serbia, ćirilica continues to hold constitutional protection as the primary script of the state, while Latin script remains prevalent in commerce, digital communication, and international contexts.

The symbolic role of ćirilica extends beyond writing. It is frequently associated with concepts of nacionalni identitet (national identity), tradicija (tradition), and duhovnost (spirituality). Campaigns promoting očuvanje ćirilice (preservation of Cyrillic) aim to strengthen its presence in schools, public signage, and media. Cultural organizations such as Matica srpska and the Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti (Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts) actively publish in Cyrillic to preserve its heritage.

Despite modernization and globalization, ćirilica remains a cornerstone of Serbia’s linguistic and cultural landscape. Its continued use reflects both respect for historical legacy and the dynamic coexistence of tradition and contemporary expression in Serbian society.

CRVENA ZVEZDA

Crvena zvezda (Red Star) is one of the most prominent sports clubs in Serbia and a major symbol of national identity, pride, and socialist heritage. Founded in 1945 in Belgrade, shortly after the establishment of socialist Yugoslavia, the club was created by the Fiskulturno društvo mladih radnika (Physical Culture Society of Young Workers), representing the ideals of youth, unity, and postwar reconstruction. The name and emblem, featuring a red star, reflected the ideology of socijalizam (socialism) and the influence of the Komunistička partija Jugoslavije (Communist Party of Yugoslavia).

Crvena zvezda’s football team quickly became the flagship of Yugoslav sports. Known locally as Zvezda, it built a strong reputation through technical skill, passionate supporters, and international success. The club’s home stadium, Stadion Rajko Mitić, popularly called Marakana, is located in Belgrade’s Dedinje district and can hold over 50,000 spectators. The stadium regularly hosts matches of the Superliga Srbije (Serbian Super League) and international competitions.

One of the defining moments in the club’s history came in 1991, when Crvena zvezda won the Kup evropskih šampiona (European Cup), defeating Olympique de Marseille on penalties in Bari, Italy. This victory made it the first and only Serbian club to win Europe’s most prestigious football tournament, solidifying its place in world football history. That same year, the team also captured the Interkontinentalni kup (Intercontinental Cup), defeating Chile’s Colo-Colo.

Crvena zvezda’s fan base, known as Delije (Heroes), is among the most devoted and organized supporter groups in the Balkans. The Delije occupy the severna tribina (north stand) of the stadium, where they display elaborate choreographies, wave flags, and sing patriotic songs such as “Marakano, naša diko” (Marakana, our pride). Their support goes beyond football, extending to basketball, volleyball, and handball divisions within the Sportsko društvo Crvena zvezda (Red Star Sports Society).

The club’s historical rivalry with Partizan Beograd (Partizan Belgrade), known as the “večiti derbi” (eternal derby), is one of the fiercest in European football. Matches between the two teams are charged with emotion, representing not only sports competition but also broader social and political contrasts rooted in Yugoslavia’s postwar structure—army vs. civilian, establishment vs. people’s club.

In the post-socialist era, Crvena zvezda has maintained its prestige while navigating economic challenges and the commercialization of sports. It continues to nurture young talent through its omladinska škola (youth academy), which has produced many players who later joined major European clubs.

DRUGI SRPSKI USTANAK

Drugi srpski ustanak (Second Serbian Uprising) was a crucial event in Serbian history that secured national autonomy from the Osmansko carstvo (Ottoman Empire) and laid the foundation for the modern Serbian state. It began in 1815 under the leadership of Miloš Obrenović, following the failed Prvi srpski ustanak (First Serbian Uprising) led by Karađorđe Petrović in 1804. The uprising took place in Takovo, near Gornji Milanovac, and is remembered as the decisive step in restoring Serbian self-governance after centuries of Ottoman domination.

The immediate cause of the revolt was renewed Ottoman repression after the collapse of the earlier uprising. Villages were subjected to porezi (taxes), odmazde (retaliations), and hapšenja (arrests), creating widespread unrest among the seljaci (peasants). During Easter of 1815, Obrenović gathered local leaders at Takovo and raised the call to arms with the words, “Evo mene, evo vas – rat Turcima!” (Here I am, here you are – war on the Turks!). This moment became one of the most iconic declarations in Serbian history.

Unlike the first rebellion, the Second Serbian Uprising was characterized by a more pragmatic approach. Obrenović sought both military and diplomatic solutions. While hajduci (outlaw fighters) and local militias engaged Ottoman forces near Ljubić, Čačak, and Požarevac, Obrenović opened negotiations with Ottoman governors. His policy of balancing armed resistance with diplomacy proved effective. By 1816, Serbia gained de facto autonomy, confirmed later by the Hatiserif (imperial decree) of 1830, which recognized Kneževina Srbija (the Principality of Serbia) as a semi-independent entity under Ottoman suzerainty.

The uprising also marked the rise of the Obrenovići dynasty, which would dominate Serbian politics for most of the nineteenth century. Miloš Obrenović became the first knez (prince) of autonomous Serbia, centralizing power and implementing reforms in taxation, administration, and justice. He founded the first state institutions, such as the Državno veće (State Council), and encouraged education through the establishment of škole (schools) and bogoslovije (seminaries).

The legacy of the Second Uprising occupies a central place in Serbian national consciousness. Monuments, such as the Spomenik u Takovu (Monument in Takovo), commemorate the event, and every year, Takovski ustanak celebrations remind citizens of the struggle for national freedom. In literature, writers like Vuk Karadžić and Petar II Petrović Njegoš immortalized the spirit of resistance and unity that characterized the movement.

The Drugi srpski ustanak thus represents not only a military victory but also a political and cultural renaissance. It signaled the rebirth of Serbian statehood and the beginning of modern nation-building. Through strategic leadership, national solidarity, and diplomatic skill, Serbia transitioned from rebellion to recognition—an achievement that reshaped the political map of the Balkans.

EVROINTEGRACIJE

Evrointegracije (process of Serbia’s accession to the European Union) refers to the comprehensive political, economic, and social transformation aimed at aligning Serbia with the Evropska unija (EU) (European Union). This process officially began in the early 2000s after the fall of Slobodan Milošević and the formation of the Demokratska opozicija Srbije (DOS) (Democratic Opposition of Serbia), which made European integration a national priority. The goal of evrointegracije is to harmonize Serbian laws, institutions, and standards with those of the EU while ensuring stabilnost, (stability), vladavina prava (rule of law), and ekonomski razvoj (economic development).

Serbia took its first formal step toward the EU with the signing of the Sporazum o stabilizaciji i pridruživanju (SSP) (Stabilization and Association Agreement) in 2008. This agreement created a framework for cooperation in trade, human rights, and governance reform. In 2012, Serbia obtained status kandidata (candidate status), marking an important milestone. The next major step occurred in 2014, when the country opened pristupni pregovori (accession negotiations) to adopt the EU’s acquis communautaire—a comprehensive body of laws covering areas such as pravosuđe (judiciary), tržišna ekonomija (market economy), javna uprava (public administration), and ljudska prava (human rights).

A critical part of evrointegracije involves regional cooperation and normalization of relations with neighboring countries, especially the Kosovsko pitanje (Kosovo question). The Briselski sporazum (Brussels Agreement) signed in 2013 established a framework for dialogue between Belgrade and Priština, mediated by the EU. Although implementation remains complex, progress in this area is viewed as essential for advancing Serbia’s European path.

Economic reforms have been another major component. Serbia has worked to attract strane investicije (foreign investments), reduce javna potrošnja (public spending), and enhance konkurentnost privrede (economic competitiveness). Cooperation with EU institutions such as the Evropska investiciona banka (EIB) (European Investment Bank) and the Evropska komisija (European Commission) has facilitated funding for infrastructure, environmental protection, and education programs, including Erasmus+ for student exchanges.

The process of evrointegracije also demands reforms in pravosuđe (judiciary), borba protiv korupcije (fight against corruption), and sloboda medija (media freedom). The adoption of EU-aligned laws such as the Zakon o zaštiti konkurencije (Competition Protection Act) and the Zakon o javnim nabavkama (Public Procurement Law) represents progress, though implementation continues to face challenges.

Public opinion in Serbia regarding EU membership remains divided. While many citizens associate the EU with bolji životni standard (better living standards) and modernizacija društva (modernization of society), others fear loss of suverenitet (sovereignty) and cultural identity. Nonetheless, the Serbian government maintains its commitment to EU integration while balancing relations with Rusija (Russia) and Kina (China).

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Serbian, we recommend that you download the Complete Serbian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't in any other textbook so you can amaze your Serbian friends with your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Serbian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Serbian today!